Busy, busy busy

Few creatures have as much on their plate (so to speak – perhaps an unfortunate choice of words!) as today's topic: chickens.

When they’re not boldly going where no chook has gone before, in search of new grubs to unearth, they’re stopping to rake the ground in long, dramatic strokes.

When that’s done there’s always a dust bath to prepare, nests to be sat upon, and a running commentary on the state of affairs to be maintained.

And all this to be coordinated with a brain the size of a pea.

As complicated as the Tudors

For such a ubiquitous critter the domestic chicken has, according to this terrific article, “a genealogy as complicated as the Tudors, stretching back 7,000 to 10,000 years”.

According to Charles Darwin, our chooks descend from Gallus gallus, the red junglefowl.

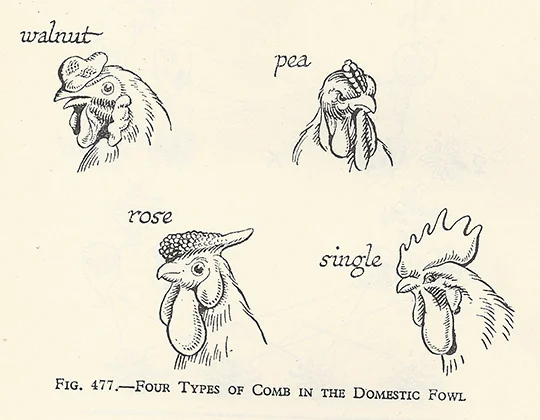

One of my favourite recent second-hand bookshop finds is Lancelot Hogben’s 1938 tome Science for the Citizen. In the chapter on genetics, a brief discussion on the inheritance of different comb types in chooks provides much needed relief from the no doubt fascinating discussion of fruit flies.

A dizzying array

If you’re into stats it may interest you to know that the British Poultry Association recognizes 92 chicken breeds, and that chickens are classified as either Large Fowl or Bantams.

Four internationally recognized breeds of chicken have been developed in Australia: Australorp, Australian Game, Australian Pit Game and Australian Langshan.

At the RNA Exhibition in Brisbane, the Poultry category continues to draw exhibitors keen for glory. Last year prizes were awarded in nearly 20 categories, each with a dizzying array of subcategories and even further classes.

There is a separate competition for eggs, with Tracy Rowlands taking out the Grand Champion Egg Exhibit of Show.

The rare Poultry Breeder’s Association of Australia holds its own annual show, with two main sections (rare Breeds and Rare Varieties) and an associated list of approved breeds, varieties, colours and abbreviations that Alan Turing would have been hard pressed to decipher.

Zen chicken

I have a colleague who confessed once to losing track of countless hours just sitting and watching his backyard chooks go about their business.

In many ways chooks are the feathered equivalent of the doctors waiting room fishtank: the constant movement lulling the observer into a state of slack-jawed peace.

The companionability of chooks has been put to remarkable use in the UK, in a programme that uses chickens to help overcome loneliness in the elderly.

In his marvellous book More Scenes from the Rural Life, describing a year of life on his farm in upstate New York, Vernon Klinkenborg explains his affection:

“Most of the birds flutter away from me as I toss out the cracked corn, and then they fall on it greedily. But there’s always one, a Speckled Sussex hen, that will let me pick her up and hold her under my arm.

Why she lets me do that I have no idea. Why I like to is easy: the inscrutable yellow eye, the white-dotted feathers, the tortoise-shell beak, and, above all, the noises she makes…I don’t know what she is saying – perhaps only “put me down” – but it sounds like broken purring.”

Keeping chickens

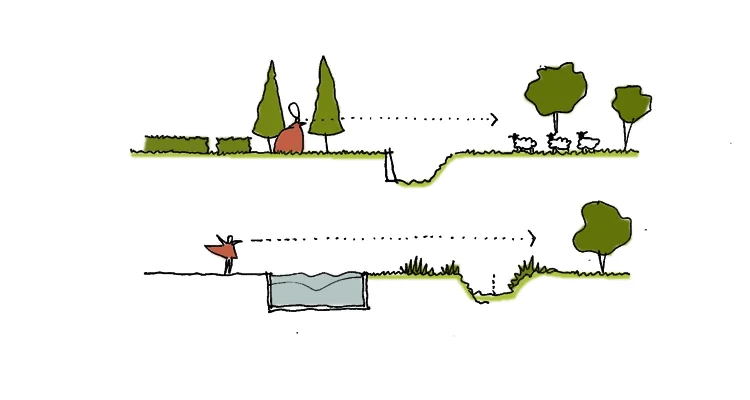

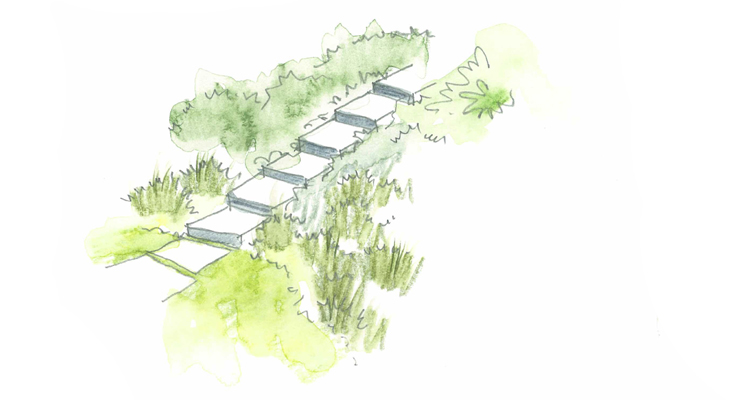

We’re designing a garden project at the moment, and finding the perfect spot to house the family’s four chickens is an important part of the brief.

Keeping chickens is remarkably easy, and there are countless books and websites (in Australia try this one; in the USA this one) that will show you how to get started. Once you’re up and running the benefits pretty much flow all your way.

In exchange for fresh water and all the kitchen scraps you can provide, you’ll have a constant supply of fresh eggs.

In exchange for safe nighttime shelter you’ll have an industrious and personable garden companion, and that’s a delight not to be underestimated.

Any of this getting' through to you, boy?

Almost single-handedly responsible for giving roosters a bad name, here's the best (or worst) of Foghorn Leghorn.

All chicken illustrations by Amalie Wright.