It came as no surprise to me that Peter Greste chose an image taken at the beach to show the world he was free after 400 days in an Egyptian jail.

Australians claim it’s the outback that makes us, but it is to the coast we cling, to the beach we flock, drawn as far out and away from the red heart of the continent as it’s possible to be.

This country has nearly 36, 000 kilometres of coastline, and the beach threads a long line through our literature and art.

In Richard Flanagan’s Booker Prize-winning novel The Long Road to the Deep North, it is to a South Australian beach that hero Dorrigo returns, as a young man before the war, and then in a lifetime of memories.

On the gallery wall Sydney’s beaches shine, from the voluptuous ladies reclining across Brett Whiteley’s sparkling shores, to the young bloke immortalised in Max Dupain’s Sunbaker.

Of course it’s a similar story in any island nation: the beach is a place of transition - no longer solid land, not quite water – and there’s something equally fragile and terrifying about such places that speaks to us.

The great gardens of history, though, tend not to be found on the coast. Garden-makers could channel water from snow-capped mountains to the desert, bend rock and stone to their will, and summon forth plants from all corners of the globe.

Just not at the beach. I wonder why?

The beauty of dunes

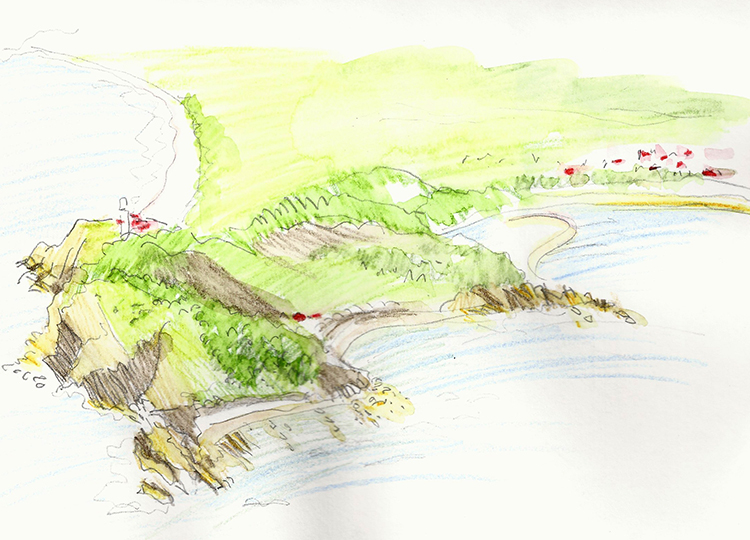

My love for the coastal garden began when I was given the opportunity to work on a project that had been designed as a contemporary interpretation of Queensland’s perched lake sand islands.

The first thing I became captivated with was dunes.

These beautiful, sensuous three-dimensional forms are a precise manifestation of the interaction between wind and sand.

Where the wind has pushed its way forward the sand eases up, long and flat. Behind, where the wind has passed over, the sand falls steeply away, at the precise angle it can support itself without collapsing.

Fraser Island’s dunes are parabolic: vast sweeping fingernails of sand created by ancient erosion of the Great Dividing Range.

Like all coastal dune systems they are exposed not only to wind, but to sun and salt. This makes the dunal landscape a very particular one for plant growth.

Dunal systems

Taking a slice through a coastal dune system reveals the rhythm and timing of its creation, and also the diversity of locations for which specific plants have adapted.

Closest to the ocean are the beach berms, the sandy dunes with no vegetation.

Behind are the incipient dunes, home of the pioneers: low, spreading grasses and creeping plants like spinifex (Spinifex sericeous) that bind and stabilise the sand with its deep and expansive roots, and trap windblown sand, allowing the dunal system to grow.

Next rise the foredunes, or frontal dunes.

This is where bigger groundcovers, small shrubs and short-lived trees start to make an appearance. The plants of the foredune are fast-growing, prolific re-seeders, and can survive periodic burial under windblown sand.

The frontal dunes sweep down to a swale and then rises up again to the hind dunes. With the protection of the dunes, long-lived trees can establish, and beneath them a more permanent array of understorey plants.

Plants of the dunes

Healthy coastal dune systems are critical buffers between ocean storms and our settlements, and vegetation is essential to maintaining healthy dune systems.

Luckily for garden-makers, coastal dune vegetation is extremely beautiful.

In the incipient dune zone we’ve already talked about spinifex, with its beautiful, silver-green foliage, but for more colour there’s the bright green foliage and violet purple flowers of the Beach Morning Glory (Ipomea pes-caprae).

The frontal dunes give us the Coastal Wattle (Acacia sophorae), the noble Coastal Banksia (Banksia integrifolia), elegant She-Oak (Casuarina equisetifolia), architectural Screw Pine (Pandanus pedunculatus) and excellently named Pigface (Carpobrotus glaucescens), amongst many others.

And moving back into the hind dunes we find the Wallum Banksia (Banksia aemula), Cotton Tree (Hibiscus tileaceus), Coastal Rosemary (Westringia fruticosa), Macaranga (Macaranga tanarius) and more.

If selecting coastal plants for your garden don’t just consider what they look like.

When Brian Ritchie of the Violent Femmes (sigh…soundtrack to my Grade 12 school camp) moved to Australia he built a house by the beach in Tasmania. A stand of existing she-oaks stood between the house and the beach, blocking views of the water but giving the musician a greater gift: the constantly changing sound of the wind moving through the trees.

Dunal plants put up with a lot, meaning there will often be a species that can handle your situation, be it fast-draining ground, hot sun, or strong winds.

They can be combined to look naturalistic, a bit shambolic and cottage-y, or sculptural and contemporary.

I bloody love them don’t you?