Sometimes it’s easy to think of designers as a weird, black-clad species that flounces around shouting “Just make it pink! I vant everythink to be pink!”

And admittedly, I’m sure there are some like that out there.

And…ahem…some of us do like black.

However for most designers, what they do is bloody hard work. Fun, and the only thing they could possibly imagine doing, but hard work nonetheless.

The sheer quantity and complexity of everything that must be considered can be enormous, even on the most seemingly simple of projects.

Today I’d like to share a landscape design exercise that I find very humbling. On the one hand, it lets complex tasks be broken down into smaller chunks. On the other, it reinforces the importance and impact of every decision we make when designing.

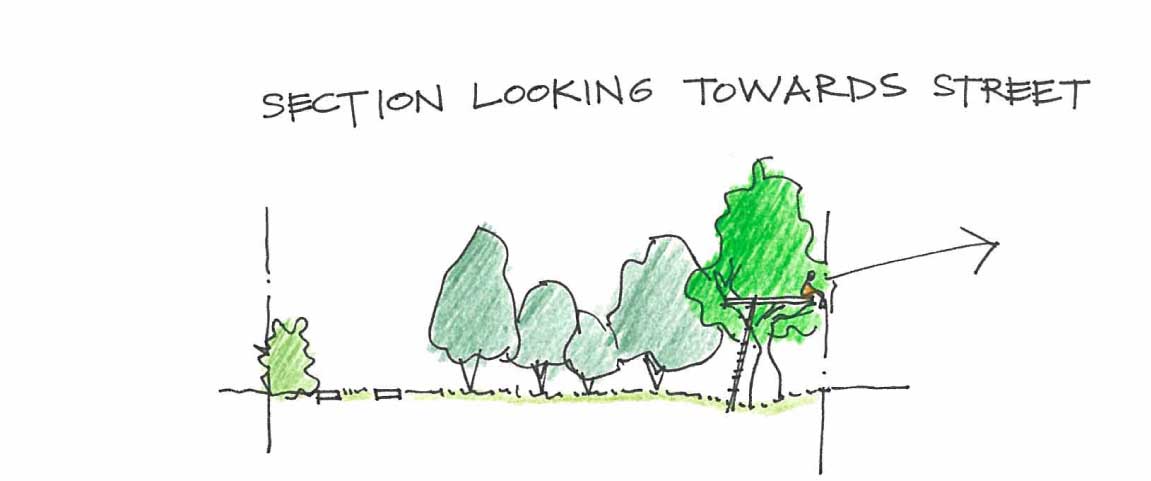

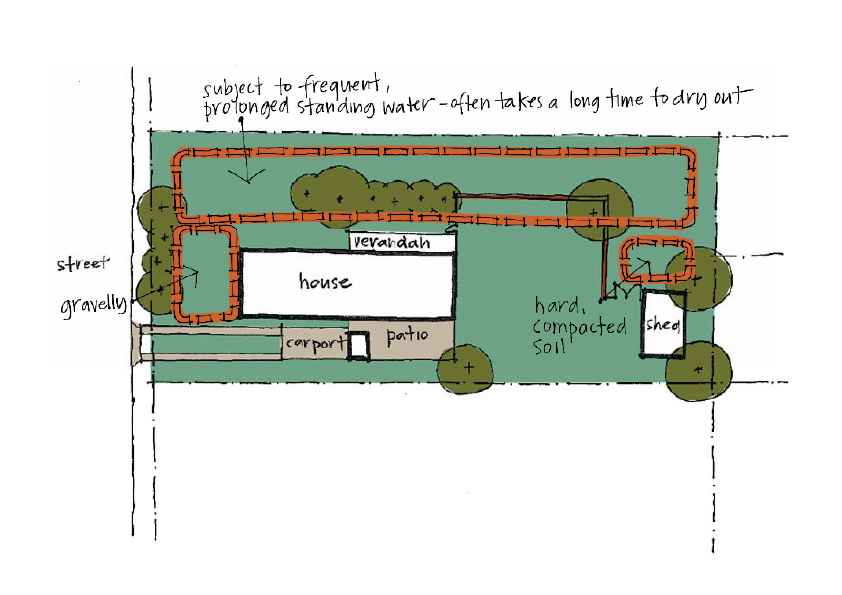

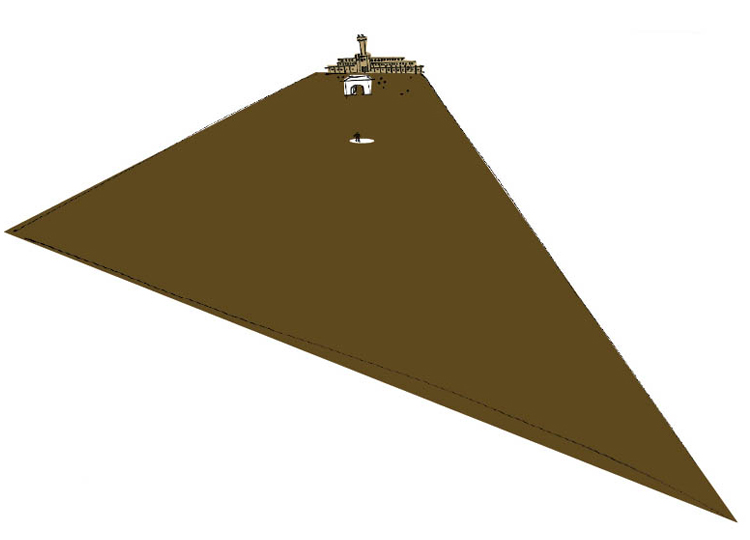

You start by imagining your favourite garden, park or street. I’m going to use the one we analysed recently.

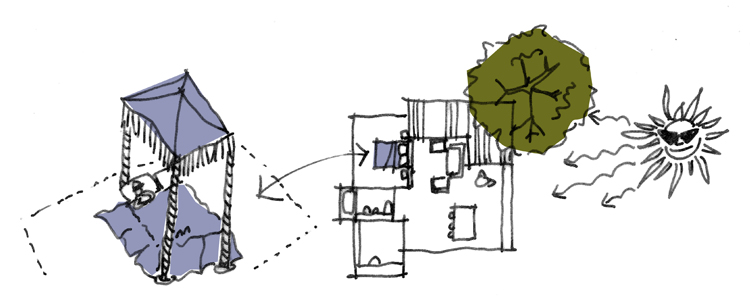

That's the house in the middle. The shed is on the far right, and the street is to the left.

Now for the fun (and tricky) part.

You’re in charge, but you’re only allowed one tree. Just one tree. (You don’t need to consider what species at this point.)

Where are you going to plant it, and why?

For me, answering these seemingly simple questions requires me to think very strategically about how the different spaces in the garden already work, and how this new tree will alter things.

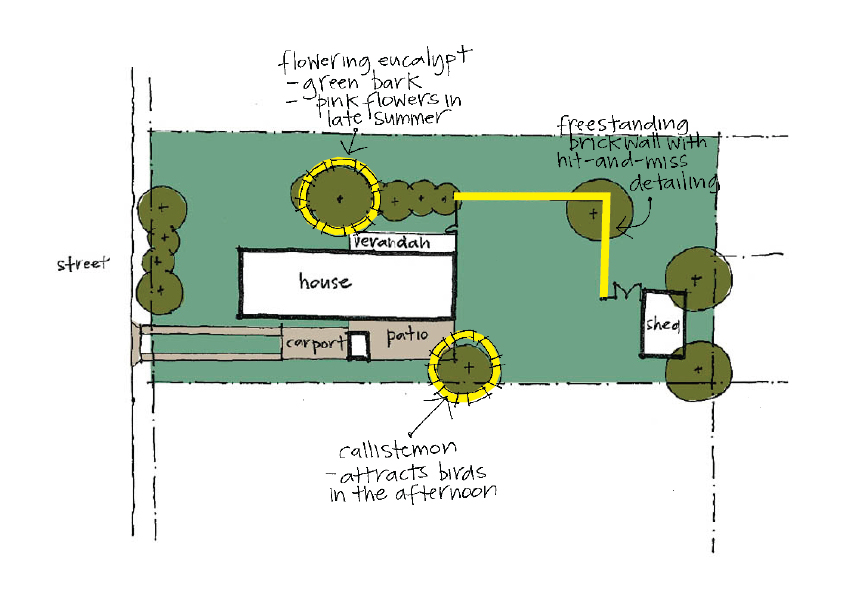

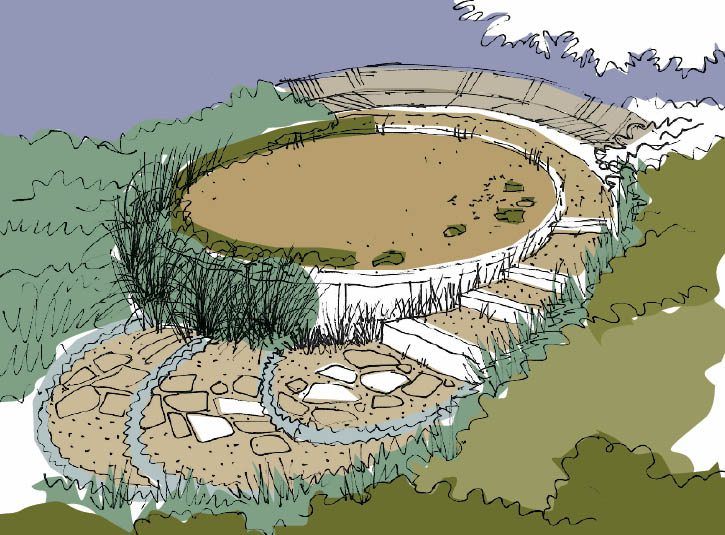

Here are a few of the options I considered:

Option 1

Placing the tree in the top left (north) corner. A tree here would provide additional privacy from the street.

As the tree grows in this location I could build a platform in the branches and see across to the lake over the road.

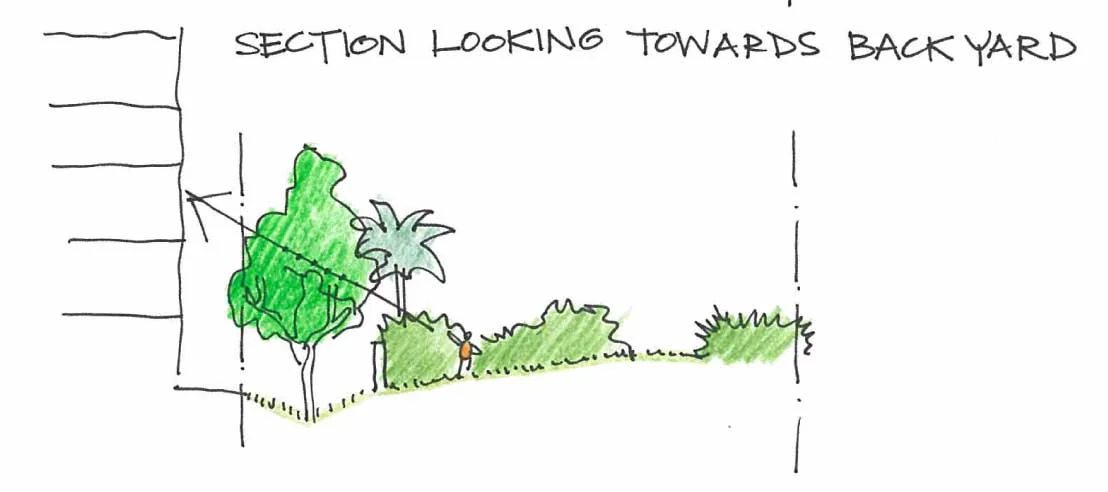

Option 2

Placing the tree between the internal screen wall and the boundary.

A tree here would help screen the back of the development proposed for next door, and would provide an element that’s closer in scale as the new multistory building.

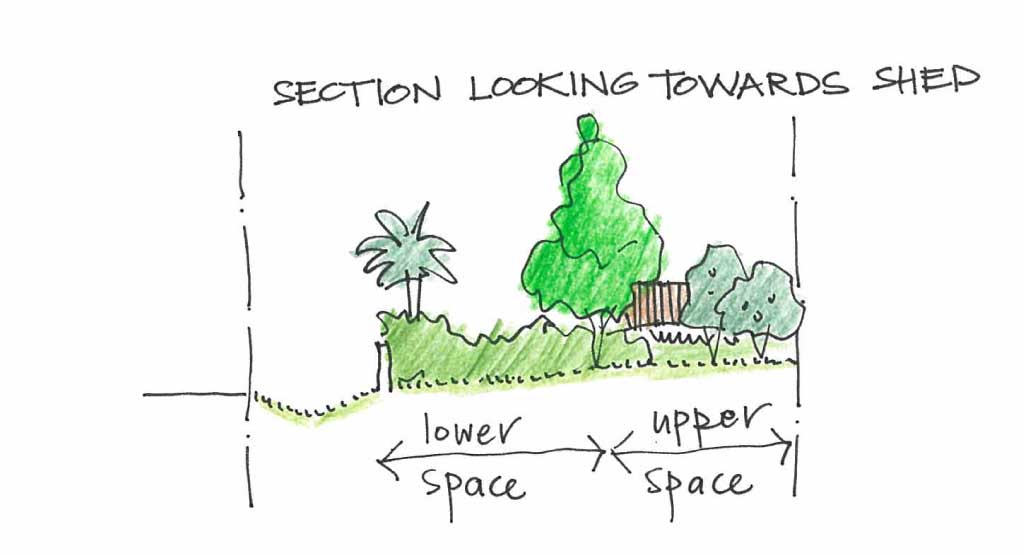

Option 3

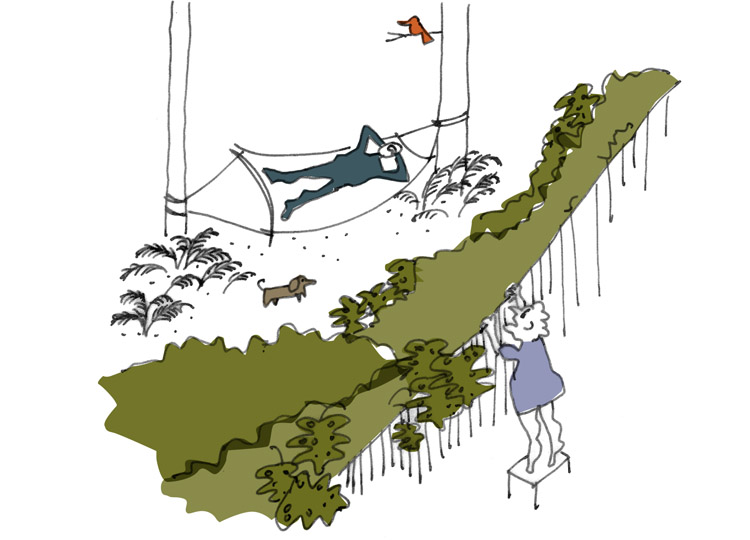

Placing the tree at the end of the existing planting, inside the screen wall. A tree here would shade the flat section of yard directly outside the house, enabling it to be used for more hours of the day.

The tree would act as turning point or fulcrum between these two sections of the garden, allowing them to read as their own particular places. This tree would also start to screen the shed, so it would be less visible from inside the house.

Each of these options creates different spaces and function in different ways. Which would you choose?

Where have you placed your tree? Why?

To really see the power of this exercise, ask someone else to imagine the same space you chose. Then, without giving away your answer, ask them where they would place just one tree, and why.

I love the one tree exercise because on the surface it seems so simple. But it’s valuable for three reasons.

Firstly, it shows that every complex design problem can be broken down into smaller parts.

Secondly, it shows that there are lots of possible solutions to even the simplest design challenge.

Following on, thirdly, it shows that every decision we make is a design decision, and the choices we make about all decisions have a direct impact on the spaces and functions of our landscapes. We do well to proceed thoughtfully.

So tell me…where did you plant your tree, and why?

ps: Let me know if you liked the coloured pencil versions of the sketches this week. (I do) Leave a comment below, or drop me a line. Thanks!